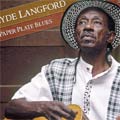

Clyde Langford

Paper Plate Blues

About

Details: Audio CD, 2005, 28 Tracks, 68mins, Produced and Recorded by Alan Govenar

Liner Notes

Clyde Langford (June 6, 1934 - )

Lightnin’ Hopkins’ older brother, Joel, taught me when I was 13 years old. He was a guitar picker, and he was sweet on my grandmother that lived with us. And he found out some kind of way that I was interested in learning to play a guitar. And that was a sure way he could get a chance to be around her. Over there, he’d show me how to play a guitar in the evening time, and after I’d get out of school. Joel was part of my mama’s daddy’s people. Not really close cousin, but maybe a fourth cousin, something like that.

The way I pick the guitar is unique to me. I use a metal thumb pick. I down strum with the thumb pick, all down strokes. That sets the rhythm. It’s a kind of percussion. Then I make my upper strokes with my fingers, my pointing finger or the next two. I pick part with my fingernails and part with the tip ends, the meat part of my fingers. I don’t use the little finger. Mostly, I tune to an open G. It’s somewhat like a banjo. I have no idea why I play that way. I just picked it up. It’s possible that I got some of it from country music and applied it to the blues. What makes it blues is bending the notes, and chokin’ part of the neck. It’s kind of hard to explain. It makes a chokin’ sound. It’s like you’re chokin’ someone with your hands around their neck and they’re makin’ a chokin’ sound.

I’ve lived my whole life near around Centerville. I grew up in the country. I was born June 6, 1934. We moved up in town the same year I started playing a guitar. When I was coming up, I kept a couple of guys with me. Sometimes I’d have three guys, another guy on a guitar, one on a set of drums. We was always playing out of town, like in Marlin or Temple … Fairfield, Palestine, Oakwood, sometimes in Crockett, that’s about 33 miles east of Centerville. Matter of fact, I used to play on KIVY over there when I was about 16 or 17 years old, every Sunday morning. That was at a radio station over in Crockett. It was just a little old local broadcasting system at the time, and different ones that wanted to perform, you could go over there, and they would let you sing, play music, dance, or if you had anything to sell, you could broadcast it [for the people who lived in the country around there]. Oh, they’d sell stuff like homemade candy – peanut brittle, syrup. Matter of fact, my manager, Bob Green, he sold a lot of syrup over there, ribbon cane syrup, and sweet potatoes, tomatoes, just different things. He’d broadcast it and let people know what days he was going to have a supply of stuff at his home and how to get there. And then they would know what day to go to Crockett to pick up something.

Oh, we didn’t play too long. Couple or three numbers, and that was it. Oh, let me see. I believe “Long, Leany Mama” and “Poison Ivy,” “How Much More Longer.” Just different numbers. You know, I can’t even really think of them. When I get my rig and start playing, all them numbers just brighten up or just picture up on my brain system, or just brighten up.

The blues can be a number of things. A lot of people tell you blues is just one thing, but blues can be a number of things. Blues is something in equivalence to a spirit. And then, too, blues is something that you make out of it whatever you feel happy. Blues is something strange, something that’s unlike anything else. And it’s so different from any other type of music. The real blues. You see, you’ve got people that’s playing music they call blues is not really blues. And it’s people singing and playing, going through the motions of that. But it’s so much different from any other kind. And some blues has a meaning to it. Some blues doesn’t even have a meaning. You just feel it, singing and playing it. The music sound good, the singing sound good, but there’s no meaning to it. I try my best to let it be a meaning to whatever I play and sing. You got [chords] E, F, G, A, B, D. I don’t read music. Just play by ear.

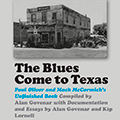

On a Wednesday morning in early October, 2003, I drove to Centerville, Texas, with the French psychoanalyst and blues aficionado Francis Hofstein and his wife, Nicole, to record Clyde Langford, a blues singer I had read about in a newspaper article and interviewed on the telephone. The morning fog was so dense that the landscape was muted and barely visible a hundred feet ahead.

When we arrived at FM 1119, the road on which Clyde lives, I couldn’t find his house. I called him on my cell phone, and he told me he’d seen me drive past twice. Finally, we got settled. Clyde pulled out his acoustic guitar at around 10:30 and played until about 2:00 that afternoon, refusing to take a break. At first, I didn’t know what to think of his guitar; the body was beat up, and he seemed to frail the strings with his metal thumb pick as if he were playing a banjo. The bridge of the guitar was loose, and the vibration of the bass strings had a strange distortion.

Clyde learned the rudiments of guitar from Joel Hopkins, Sam “Lightnin’s” older brother, but he was clearly influenced by country music as much as blues. Growing up, he loved to listen to the radio and tried to imitate what he heard, adding his own distinctive interpretation. He never played much in public, preferring instead to keep a day job and to entertain himself, his family and friends at an occasional dance in town.

About a month later, after editing the recordings, I was still uncertain about Clyde’s guitar and decided to go back to Centerville to record him again with a different instrument.

Finally, after listening to these new recordings, I realized that changing guitars did not significantly alter his playing. While the buzzing vibrato of his guitar was unusual, it seemed to have an African-sounding tonality.

In between songs, Clyde often paused to tweak his tuning, reaching back into his memory for another song and taking the time to share anecdotes and stories about his life and musical influences.

– Alan Govenar